Why?

In the past six years, my professional life has been increasingly immersed in the realm of Machine Learning (ML). Despite my background as a Mathematician, I leaned into Machine Learning during my MDS (Masters of Data Science) studies. These recent years have witnessed remarkable strides in AI and ML, exemplified by the transformative impact of ChatGPT within just 18 months of its launch. Professionally, I assumed the role of program head for the Grad Certificate in Business Analytics, dedicating significant effort to refining and updating the curriculum. Additionally, my involvement in the AI Management track for the IT Management diploma means that I spend a lot of my working time explaining the role of Machine Learning in modern business practices. Whew! That was a lot of exposition!

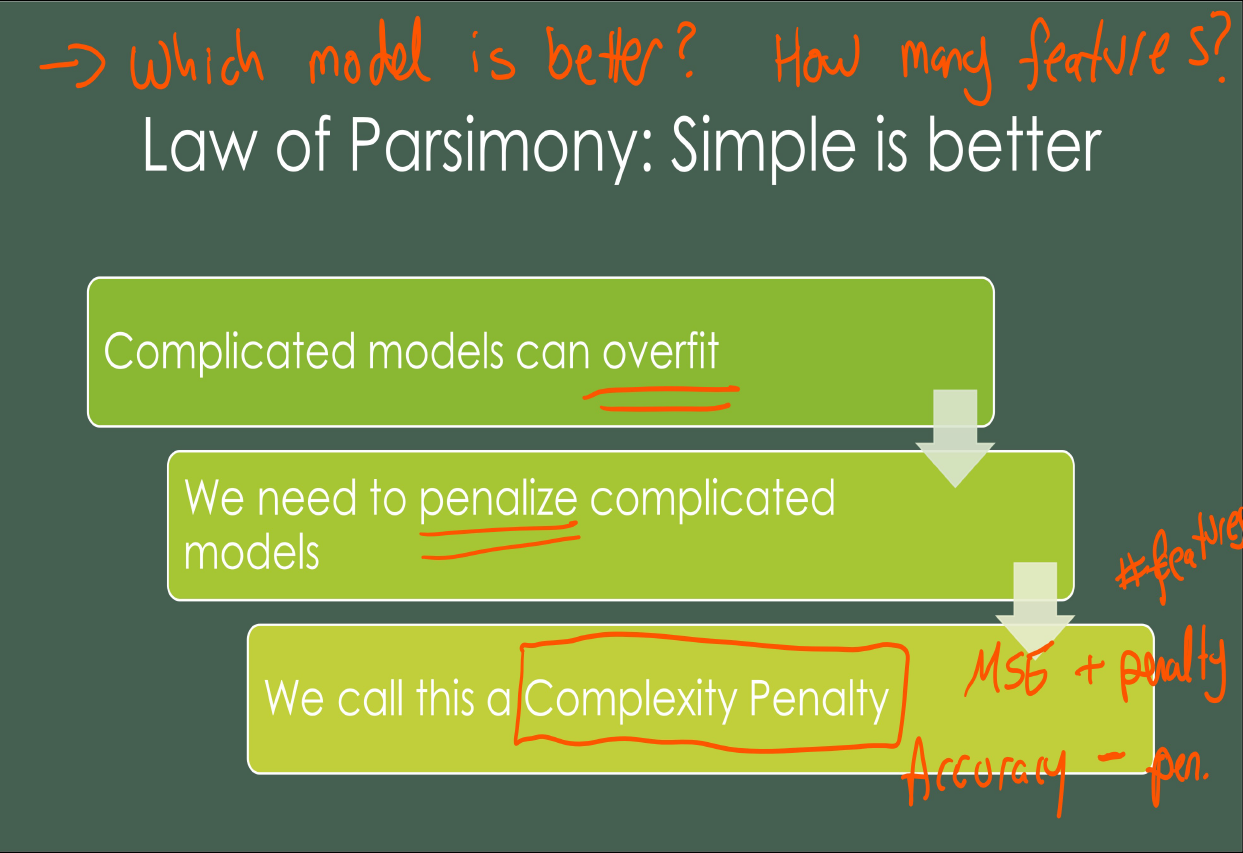

An interesting moment occurred when I had the opportunity to teach a graduate class at UBC focused on analytics, tailored for Economics students. To my surprise, I encountered resistance. The principles I advocated, emphasizing the elegance and strength of parsimonious models, clashed with the complex models aiming to capture as many variables as possible that they learned in Econometrics. Despite my insistence on simplicity for robust modelling, scepticism prevailed.

The students insisted about the necessity of incorporating more features to enhance comprehension and understand all possible explanations. Even when we explored techniques like Feature Engineering using Principal Component Analysis, confusion lingered.

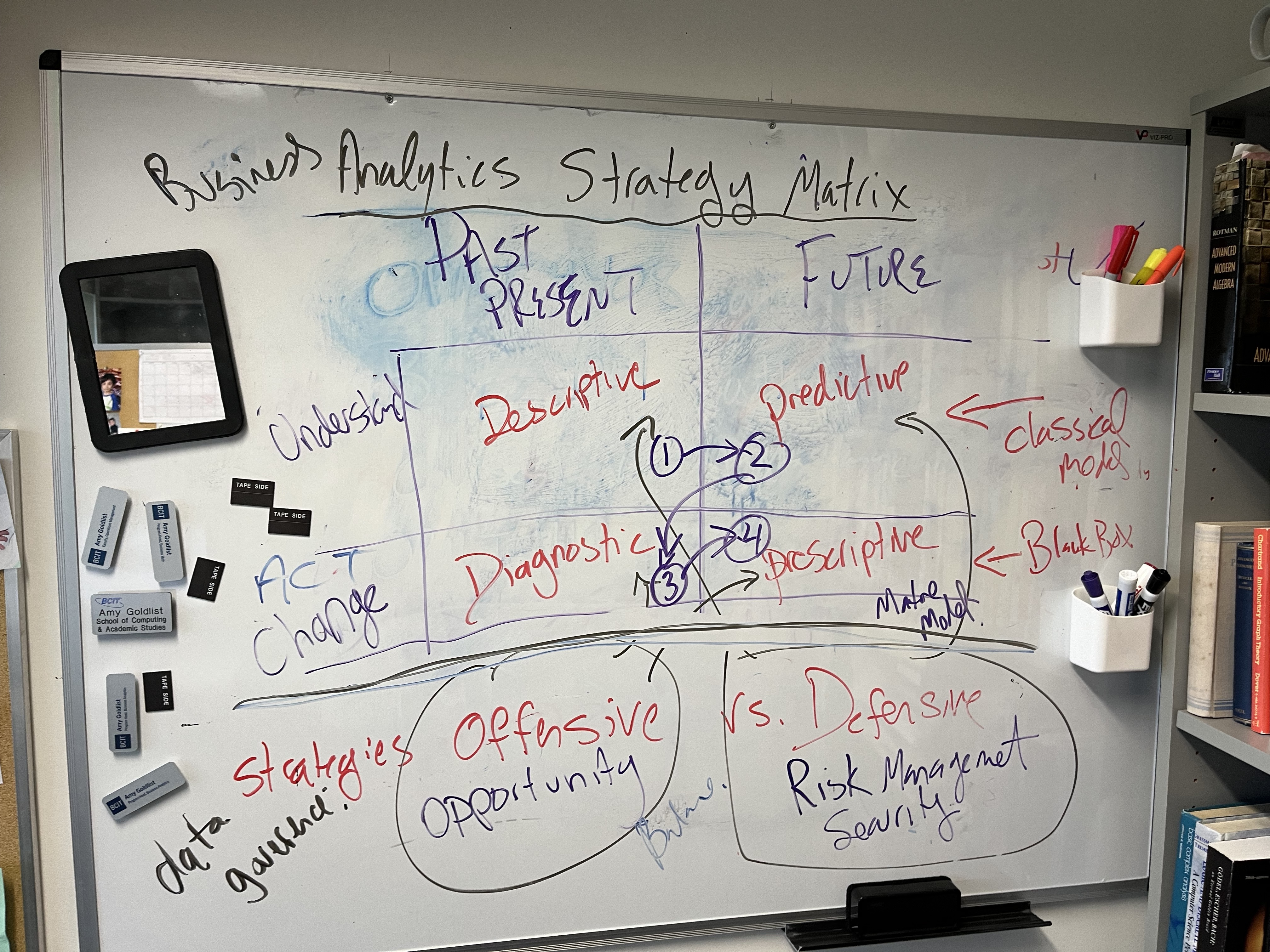

Reflecting on this class prompted me to reevaluate my approach. I am trying to bridge the divide between traditional statistical and economic methodologies and contemporary data-driven techniques. Thus, I embarked on crafting a framework that synthesizes these disparate methods, grounded in the foundational principles of Business Analytics. Drawing inspiration from the four stages of Business Analytics, I devised this framework anchored in two fundamental elements: Timeframe and Action Type. This has been clarified with my AI students, who helped me to refine my approach. This framework serves as a guiding compass, enabling a nuanced understanding and application of diverse analytical methods.

In essence, my journey has led me to develop a framework that seeks to reconcile traditional paradigms with emerging methodologies, facilitating a holistic approach to data analysis and decision-making.

The four strategies of Business Analytics

- Descriptive Analytics: What is happening now, why is that?

- Diagnostic Analytics: What should I be doing differently?

- Predictive Analytics: What will happen?

- Prescriptive Analytics: What should we do?

A motivating matrix:

We ask two important questions:

-

What timeframe are we looking at. Are we looking at the Past or Present? Or are we looking towards the Future? In other words, am I looking at the Current State, or the Future State?

-

What are we looking to do? Are we looking to Act on what we have learned? Or are we looking to simply understand? The methods that we use are going to depend on what we will do with what we learn:

| Past and Present | Future | |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding | Descriptive Analytics | Predictive Analytics |

| Action | Diagnostic Analytics | Prescriptive Analytics |

Understanding versus Action

This lies at the heart of the choice between classical methods and ML methods. When we are creating a model, we are looking to learn something. Let’s go for an example. Say I am trying to predict sales of swimwear in Canada.

Classical Methods are grounded in understanding and explaining:

Descriptive Analytics:

This is the type of thing you learned about in Statistics - we summarize data by finding the Mean, Median or Mode, we find the standard deviation or InterQuertile Range, we graph the data. I’m being very glib here, this is a lot of what I spend my time on (see: The textbook I wrote on Statistics). Here, I can compare my various variables (features in ML). Do floral swimsuits sell better when the weather is good? When the economy is bad? This is a lot of where econometrics lies - in exploring what factors affect each other.

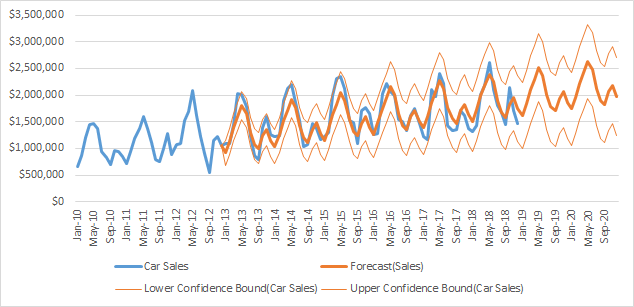

Predictive Analytics

In a classical Holt-Winters Timeseries forecast, we create a model which predicts future events (FUTURE/ UNDERSTANDING). It can tell us what will happen, but the model is more than the predictions which it spits out. The model itself gives us important information. It gives us three factors: The Trend (Are we increasing or decreasing, on average, in the long term?), Seasonality, (Is it periodic over a small amount of time?) and Cyclical (is there a second, longer periodicity?).

Our Holt-Winters model might give us:

- There is an upwards trend in Sales, that is, our Sales are overall increasingly

- Sales of swimsuits have a strong seasonal trend - Over a year, sales are highest in Spring and Summer, but drop in Fall and Winter.

- Cyclical: Swimwear styles change, and over many years a specific model (say floral patterns) will become trendy, than drop again.

ML methods are grounded in application

And can be a bit of a black box around understanding.

Diagnostic Analytics

Maybe my floral-patterned swimsuits just haven’t been selling. In descriptive analytics, we explored why that might be, but now what I want to know is what should I have done. Should I have sold striped swimsuits? Parkas instead? Given the current state, what should I have done? Here, it’s enough to come up with an option, it’s less important that we understand the root causes. (And yes, I know I’m twisting this just a bit to fit my model. Bear with me!)

Prescriptive Analytics

This is where ML really shines. It says, “What should we do?” A neural network can accurately predict future sales, but unlike the Holt-Winter’s model, it doesn’t tell us anything about why. It just gives us the tools to act. Though we can use Classical Models, we can often get better performance from a Black box.

Why is this Business Analytics?

Business Data Analytics is grounded in the needs of a Business. If you go back and read my Stats book, you will notice that we end every hypothesis test with “Make a Business Decision”. This decision making process is what really sets Business Analytics apart from data analytics. If we show that there is a Statistical difference between an new process and an old process, but the new process will only save 5 minutes a year, we won’t switch. Any question we take on comes with a built in question, what action will we take.

If I know that I will never climb Mount Everest (among other things, I’m afraid of heights), it makes sense that I shouldn’t start to train for it, unless that’s something I enjoy. At the root of any Business problem is the assumption that at the end of our process, we will be able to make a better decision than without our investigation. Again, that’s a confusing way of saying “What will we do with this information?”

Summary

Do we want to know, or act? Are we trying to act in the future, (with all of its unknown future variables), or are we doing it now? Do we need clarity in our models, for regulatory or other reasons? Is it all right if we get a better prediction, but without knowing how we arrived at it?

I hope this gives you some food for thought. It’s the “No free lunch” principle. ML methods can give us better predictive power, but that comes at the expense of understanding and clarity.