Introduction

Shadow Profile: It sounds like a dossier that a spy would have in a film from the cold war era. Though the name is dark and sinister, this collection of information that Facebook holds about many people – whether they are members or not – is simply data that Facebook has gathered from various sources, legally, maybe, but is it ethical? I’ve read articles, and researched privacy rights, and have come to the conclusion that the practice of keeping shadow profiles of data that users did not supply about themselves is unethical because the true “owner” and decision maker about data is the person the data is about; this practice violates reasonable expectations of privacy, and because the right to privacy is a human right.

What is a shadow profile?

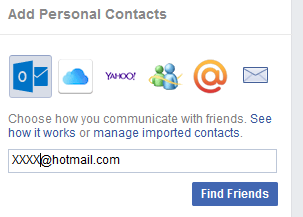

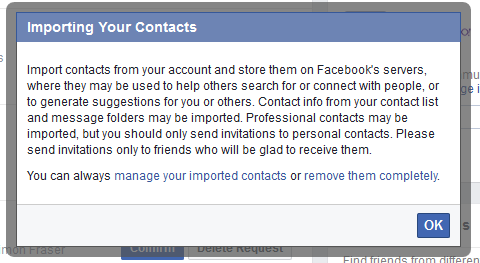

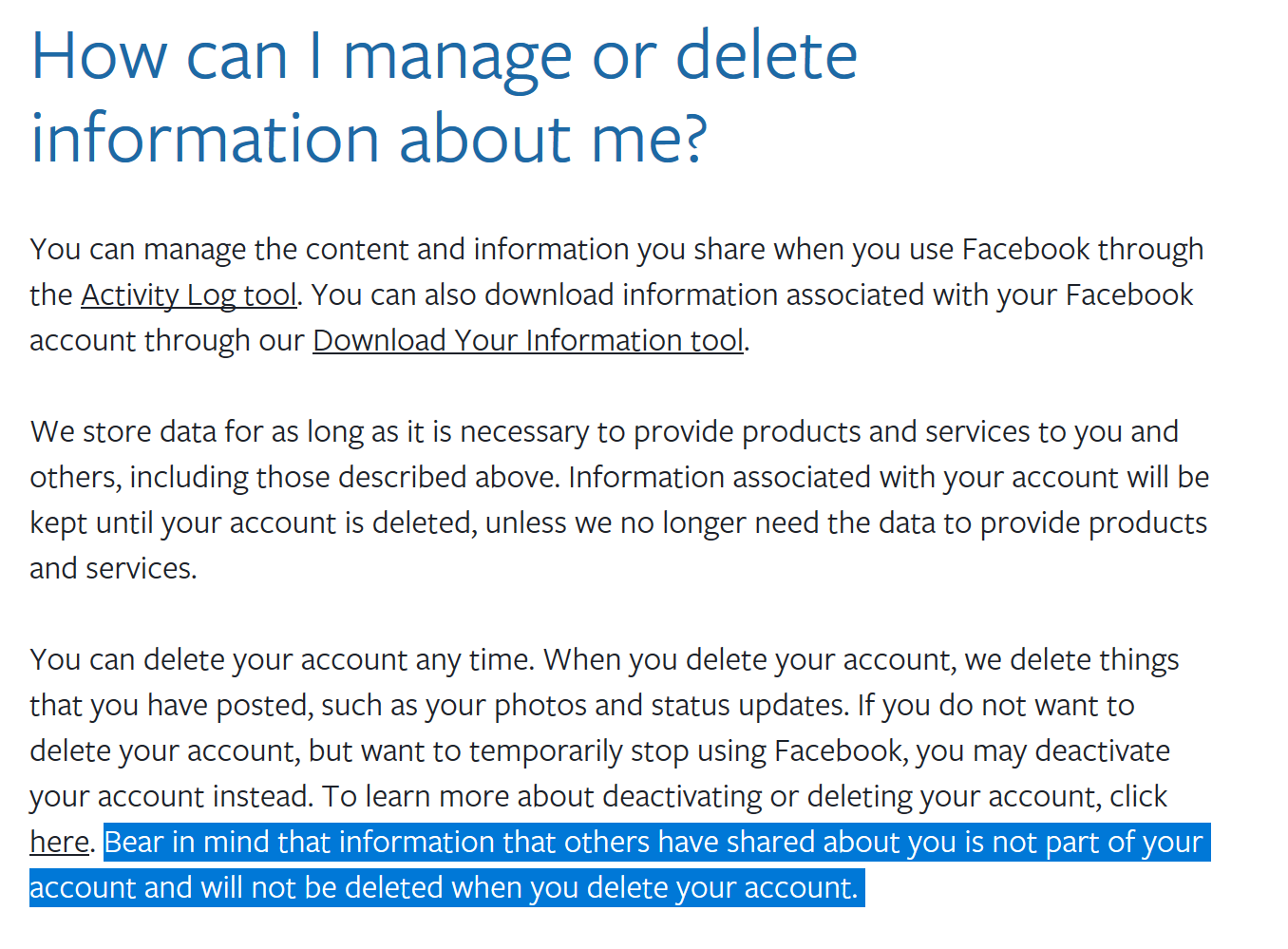

Before we explore the ethics and morality of shadow profiles, we should properly define all of our terms. When you sign up for Facebook, you agree to a set of terms which gives them permission to use your data. Whether or not people read the terms of agreement, and whether it is legally binding is not the subject of this essay. Hidden in the fine print of Facebook’s data policy is this little gem:

which states that Facebook is collecting and storing data that other people provide.

In 2013, a bug caused data about friends to be included in Facebook’s “download your data” function [Knibbs]. Though Facebook fixed the bug, it became apparent that Facebook was storing a lot of information about all of your contacts: information that the subject never uploaded in the first place. Data that is pieced together from information that lives in other people’s address books. What this means, is that even though I have never shown Facebook my phone number, it is likely that that information, along with my work email address, my alternate contacts, all exists in what was dubbed a “Shadow Profile”.

“That accumulation of contact data from hundreds of people means that Facebook probably knows every address you’ve ever lived at, every email address you’ve ever used, every landline and cell phone number you’ve ever been associated with, all of your nicknames, any social network profiles associated with you, all your former instant message accounts, and anything else someone might have added about you to their phone book. As far as Facebook is concerned, none of that even counts as your own information. It belongs to the users who’ve uploaded it, and they’re the only ones with any control over it.” [Hill]

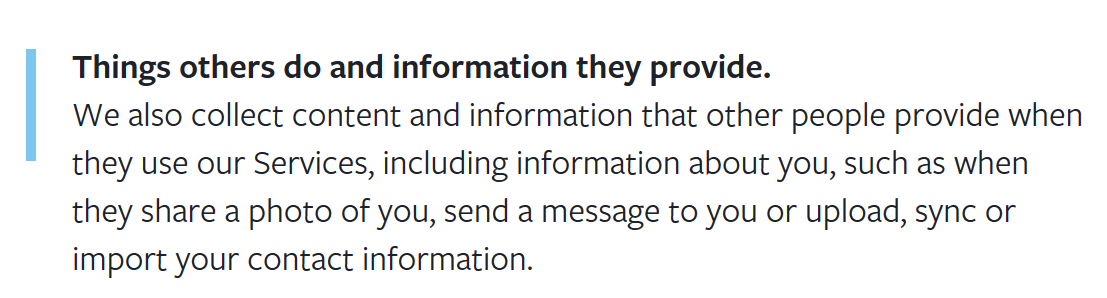

How does this process work? One of Facebook’s features is called “People you may know”:

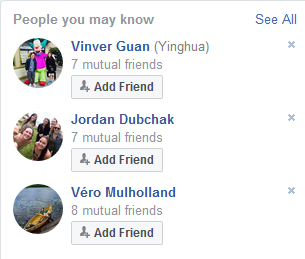

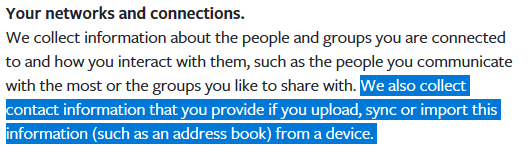

which uses data from your own profile and the shadow profile that others have uploaded to generate a list of people who you may know. In the above image, the three top friends have been selected for me based on the fact that we have friends in common. However, in order to make this list better, Facebook asks you to turn over information from your email or phone contact list.

If you authorize this feature, on your phone or computer, Facebook will take all of the data from your contacts and store it under your profile. Facebook does warn you that some people, such as professional contacts may not be people that you want to be linked to, but it still stores that data, and uses it in its black box algorithms.

In laymen’s terms, this means that data you have about other people is your responsibility, and Facebook can use it. Notice that it doesn’t have say that the contacts have to be members of Facebook. In fact, though the terms observe that others may have uploaded data about you, it may also have data about people who never even joined Facebook.

Who owns my data?

At the heart of the Shadow contact debate is ownership of data. Who owns the data about me in the Shadow Profile? According to Facebook, not me. Instead, the information is owned – in pieces – by anybody who has added me to their contact list. This means family and friends, but it also means former students and coworkers. It means my hair stylist who got my number from the salon system so she could text me to let me know her availability. It means the other parents from the multiples parenting listserv which I subscribe to (Vancouver Twins and More, if you’re interested). It means the superintendent of the building where I dropped my keys down an elevator shaft last year.

According to the Facebook terms of service, all of these people have the right to give my data to Facebook, and it will only be deleted when and if each of these people decides to. It also means that I have the right to upload information about all of the people in my phone. Right now, this includes, but is not limited to: my old real estate agent, several coworkers, my children’s friends’ parents, my brother’s ex-girlfriend, my kid’s swim instructor, a friend-of-a-friend’s daughter who we tried to hire as a babysitter, but it didn’t work out, my dentist, my parent’s Rabbi (I have no idea why that’s there), my son’s teacher, and a few names I don’t recognize. I have the power to add all of these people into Facebook, whether they are members or not.

From an ethical standpoint, I feel that this is wrong. If I give my name and email address to a company in order to get mailed a 10% off coupon, it does not give them the right to publish my contact details on a public webpage under the heading: “People who are interested in embarrassing product.”. Likewise, when I give my information to a friend or colleague, I do not expect them to write my number on a bathroom wall.

Reasonable Expectation of Privacy

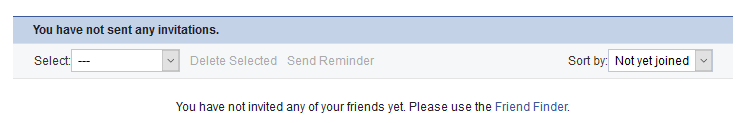

What if you aren’t a member of Facebook? Though I have not granted Facebook access to my contacts, when I look through my own account, I noticed that I can search by “Not yet joined”. This is proof that Facebook is storing data about people who are not members of Facebook, and so did not sign a user agreement.

These users have a right to their privacy, they have a right not to have their and information on Facebook’s servers.

An important part of law is reasonable expectations. Though I am not arguing through the law here, I do feel that this violates the expectation that Facebook isn’t using data about people who did not agree to their terms of service. It is not unreasonable to expect that other people don’t have permission to disseminate my information, and that I should have control of who has my private data. I would argue that exchanging phone numbers with my son’s teacher, so that we could discuss his behaviour in the classroom does not give me the right to share her number with Facebook.

Using Data in a manner for which it was not intended

Since Facebook shadow profile data is not freely available (in Canada at least, maybe not in Europe), it is hard to know how the data is pieced together and stored. A not unreasonable assumption (given as granted in the 2017 article [Hill]) is that Facebook is collecting data from disparate sources, and piecing them together to get a full profile. That means that it is not as if my work email is associated with a coworkers account, my cell phone number with my hair stylist, and never the twain shall meet. Instead, it most likely means that Facebook has been able to assemble all of the data about me (including photos and videos of me) to make one complete picture.

It is fairly likely that they have this type of data on almost everyone, whether they are Facebook users or not. In this case, the public profile, used in machine learning algorithms such as University of Cambridge’s Apply Magic Sauce [Magic], are not giving the full picture of what Facebook actually knows. In fact, though this algorithm can be quite accurate, the picture that Facebook actually has of us is much more complete than just the data we have handed to it.

Privacy as a Right

Even though this story became popular recently, and stems from the 2013 bug, it turns out that reports of “alternate data” stem back to a complaint against Facebook Ireland in 2011, as reported in the blog Schneier on Security [Shneier]. At that time, it was alleged that Facebook’s practice was contrary to EU laws, and as a result, Facebook EU seems to give you more access to your data than in North American. To me, this is an admission that Facebook’s policy is not up to the standards of European law, even before the GDPR was introduced.

As quoted in [Floridi], the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) specifically mentions safeguarding “the transfer of personal data within a group of undertakings”. It is my opinion that Facebook’s policy of keeping a shadow profile runs counter to the spirit of the GDPR. Floridi uses this to argue that privacy is a human right, and is essential to human dignity. I posit that legalities aside, Floridi is correct, and the right to control your own information is integral. I feel that by associating data about a user with other users, Facebook is violating our fundamental right to privacy.

Conclusion

There is ample evidence that Facebook is keeping data on people, and storing it (in separate pieces) with many users who may or may not have the subject’s permission to share this data. This association or “ownership” of data with people other than the subject of the data violates the right to privacy. In a modern world, where data is being used in black box algorithms for decisions ranging from credit approval to job offers, it is important that we are all able to make our own decisions about our data. Facebook may or may not be in violation of the law, but it is clear that they are using data in an unethical fashion, and for what reason? To be able to suggest friends? It is more likely that they are using this data in ways which it was not originally intended.

References and Works Cited

“Facebook”. Online, available: www.facebook.com, including Data Policy. All screengrabs are from my account, downloaded in March, 2018, on a PC running Firefox. All of the highlighting is mine.

[Floridi] Floridi, Luciano. “On Human Dignity as a Foundation for the Right to Privacy”. Editor Letter, Philos. Thechnol. Springer, April 2016.

[GILC] Global Internet Liberty Campaign. “Privacy and Human Rights: An International Survey of Privacy Laws and Practice. Online, available: http://gilc.org/privacy/survey/intro.html.

[Hill] Hill, Kashmir. “How Facebook Figures Out Everyone You’ve Ever Met”. Online, available: https://gizmodo.com/how-facebook-figures-out-everyone-youve-ever-met-1819822691, November 2017

[Knibbs] Knibbs, Kate. “What’s a Facebook shadow profile, and why should you care?. Online, available: https://www.digitaltrends.com/social-media/what-exactly-is-a-facebook-shadow-profile/, May 2013.

[Schneir] Schneir, Bruce. “Discovering What Facebook Knows About You. Online, available: https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2011/10/discovering_wha.html, October 2011.

[UN] United Nations. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. General Assembly, resolution 217 A, December 1948.

[Magic] University of Cambridge, “Apply Magic Sauce”. Online, available: https://applymagicsauce.com/.